Built to Last: Immortality Practices for Teams and Organizations

Jan 02, 2023

If you ask a Fortune-500 CEO what their most important goal is for their business, I bet you’d hear something like: “I want to build long-lasting, responsive systems that work for everyone.”

In one word, leaders crave to leave a legacy of sustainability.

Humans have a long history of building things meant to outlast them - combining principles of endurance, durability, and aesthetic timelessness. We see this in architecture, cultural artifacts, stoic teachings, and manufacturing. Intuitively, we know what sustainability is - but, I believe we have sustainability backwards.

Sustainability is often treated as a convenient ‘nice-to-have’, but not a ‘need-to-have’. Companies large enough to have departments devoted to sustainability - usually environmentally-focused - view them as translators of complex federal and local environmental laws intended to harmonize the business and their global eco-footprint. However, sustainability is bigger than the environment - this is just the area in which the lack of sustainability has had the most egregious impact. Sustainability is what allows the system to work for the most parties - for the longest.

In the Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, Stephen Covey highlights the critical balance between ‘production’ and ‘production capability’. It is a difficult balance to maintain, but the sacrificing of sustainable practices (production capability) for short term increased profit (production) is where the wheels start to fall off the wagon. This happens when organizations fall victim to one of three imaginary lines that create distance between parts of business operations that are, in reality, inseparable.

Line 1: What is ‘Inside’ the Company, and What is ‘Outside’ Of It

True sustainability is not a ‘best practice’, it is an identity.

Business has a cutthroat, competitive element that has catalyzed progress in some areas, but a tyrannical approach has been adopted in other areas to facilitate this. “Everything outside our walls is the enemy, and if it doesn’t represent money to be made, then it is useless.” However, the organization only exists in relation to what is ‘outside’ it, and therefore, it is just as important as what is ‘inside’ it.

There are relationships everywhere - between employee and employer, customer and employee, environment and supplier, board and executives, etc. Once a company realizes that their entire organization lives within the bounds of these relationships, taking advantage of others no longer seems to make sense. When the company knows that it does not benefit from relationships, rather it is relationships - sustainability no longer becomes an action to perform, but an identity to embrace.

The cart has been placed before the horse. Companies are created and then we attempt to make them sustainable. It is much more effective to make them sustainable from the start, by committing to sustainability in the original mission and every step thereafter. Instead of having a sustainability team in place to deal with environmental compliance issues, our companies should be environmentally compliant because of our commitment to sustainability.

When we recognize that we are always in relationship with our environment, the imaginary line separating ‘us’ and ‘them’ disappears. To achieve the highest possible impact over time we need to limit the amount of friction by changing the question from “Does this work for me now?” to “How long will this work for us?”.

Here are a few questions you can ask your team to begin a conversation on sustainability:

-

Is sustainability at the forefront of the decisions we make?

-

How long can our systems last?

-

Are our relationships productive for all parties involved, even those we previously considered ‘outside’ our company?

Line 2: Between the ‘Now’ and the ‘Later’

Every problem you view as a ‘later’ problem, is someone else’s ‘now’ problem.

We can’t hold off the inevitability of change. No matter how robustly our system is built, there will come a time when it needs to be rebuilt. Whether we slap a band-aid on it or invest in sustainable change likely won’t matter to us. In either case - we have made our temporary ‘now’ problem go away for a while. Don’t be fooled - it still matters which one we choose, for our legacy as leaders is not in how many problems we solve, but in how long our solutions last.

Sustainability sometimes implies sacrificing present day gains for future ones, the difficulty of which is relevant to anyone who has ever skipped a workout or ate a donut. The problem is, when you eat too many donuts, you are the only one who feels the consequences. Within large organizations, a leader can make short-term unsustainable decisions knowing that they will be long gone before the consequences are felt. It’s a slippery slope, and precisely why sustainability must be the driving force behind every business decision rather than a convenient environmental publicity move.

If you want to be healthy, long-term health must be placed at the forefront of every decision you make. You can’t simply allocate a specific time to be healthy, nor can you pay someone to be healthy for you.

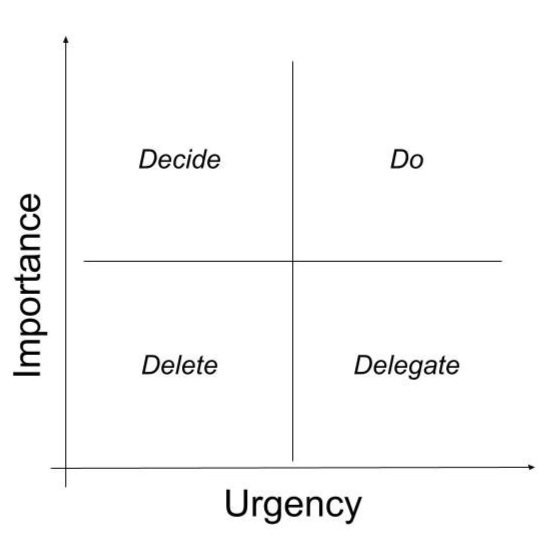

To avoid this trap, I recommend a slight shift in priority. Many people are familiar with the prioritization matrix known as the Eisenhower model. If you’re unfamiliar, you most likely use it intuitively anyways, but it is below for reference. The basic premise is that trivial tasks that pop up should be delegated to others or deleted from the docket all together, whereas important tasks should be completed by you either immediately or after some thought, depending on the urgency of the situation. This can be a tremendously useful model for those who feel swamped.

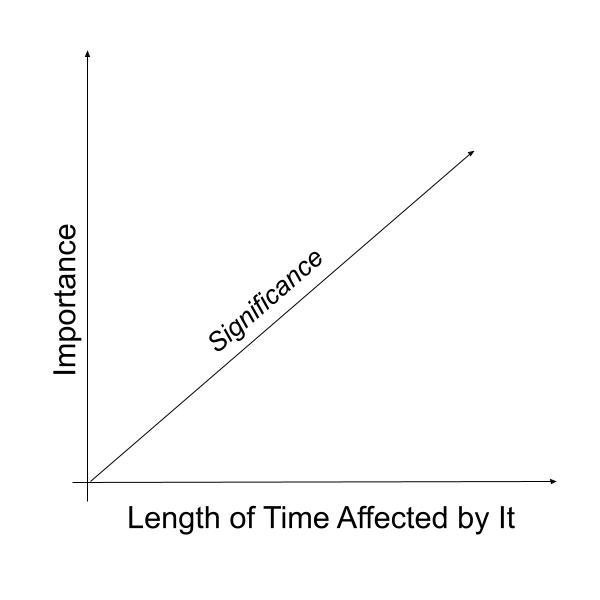

However, the gap in the model is that it fails to account for the quality of solutions delivered. Its sole purpose is to get problems off of your plate as efficiently as possible. Instead, I challenge you to take it a step further by assigning priority based on the Rory Vaden Significance Calculation (below). This model dissects the ‘importance’ axis further, not only addressing how important the issue is right now, but also how long the issue will affect your organization. The former model is focused on the time it will take to solve the problem, whereas the Rory Vaden Model is concerned with how long the solution will last. This small shift in thinking, compounded, can create long-term change throughout an entire organization.

Both models achieve the same end - prioritizing problems to be solved - but the Rory Vaden Model is a more sustainable approach because it considers the long-term effects of the developed solutions.

Line 3: Between ‘Sustainability’ and ‘Unsustainability’

Sustainability is a gradient, not a badge.

All businesses in existence are sustainable, the question is for how long? There is no magic threshold reached between a sustainable business and an unsustainable one. Individual businesses have never lasted as long as the markets they serve. Blockbuster didn’t last as long as the movie industry as a whole. You won’t last as long as humanity (I hope). It follows that a truly sustainable business is one that can close the gap between where the world is heading and where they are. Zero-gap companies are creating the future themselves (think Apple in 2007, or Tesla in 2017) while large-gap companies are altogether out of sync with the industry they serve.

Closing the gap is difficult, because it requires some forward thinking and constant change. We can’t set it and forget it, because the landscape is constantly changing. Sustainability is the peak of responsiveness, not the lack of need for it. Let’s shift from conceptual to case study… Take Tesla Motors, they are in an industry that clearly has a future: the electric vehicle (EV) market. They have attained virtually zero-gap, meaning they continually redefine the industry itself. Most importantly, sustainability is a core part of their mission. It is not an award they receive, nor a rating they achieve. They know that as the very definition of sustainability changes, they must constantly be reinventing to maintain sustainability - every day.

After the groundbreaking Model X Crossover went into production, Elon Musk was not happy with its success. It was developed with many unnecessary bells and whistles that made consumers smile but had drifted too far from the core mission of Tesla: ‘to accelerate the world's transition to sustainable energy.’ Elon lamented the unsustainability of the Model X, and even though critics were raving in its favor, he corrected the error. Sustainability breathes in every decision Tesla Motors makes, and that is a huge part of what has made them successful. How successful, you ask? The stock price has increased 800% in two years, definitively quantifying the value the consumer market sees in Tesla’s sustainable vision of the future.

There is no promised land of sustainability. There is no place you can reach where you are finally “good”. There is only the ever-present challenge of closing the gap, and aligning where we are with where we want to be. Not just in the environment, but in HR, in sales, marketing, executive leadership, and all other domains of business relationships. The difference between businesses that accept this responsibility and those that ignore it can be seen throughout history.

These illusions we have explored can drive fears that even the smartest leaders fall victim to. It is not the lines themselves that cause a company to fall into unsustainable practices. It is the fear of what is across those lines. The fear drives us to pull back and lose trust, and hunt for short-term wins that keep us safe tomorrow, yet are unsustainable by next year. If we place our full trust in sustainability, across the board, there will be short term losses. But the alternative is far worse - to be stuck on this hamster wheel, constantly reacting, but never truly responding to the changes of the world around us.

Works Cited

-

Covey, Stephen R., et al. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change. Simon & Schuster, 2020.